The Global Impact of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)

The EU has been a global leader in climate change strategies and its European Green Deal aims to make Europe the first climate neutral continent by 2050. All 27 member states have pledged to reduce their emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to levels in 1990 to help achieve this goal. While the EU is taking considerable climate action, climate change mitigation also requires stringent action on a global scale in order to be fully effective. Ambitious goals from only a single stakeholder can create the risk of “carbon leakage,” which occurs when producers displace emission intensive production from countries with strict climate regulations to ones with more lax climate standards. Carbon leakage is a common occurrence driven by cost savings for producers and can contribute to higher global emissions. To address this issue, the EU announced last year a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism aimed at avoiding carbon leakage from the EU and promoting emissions reductions worldwide.

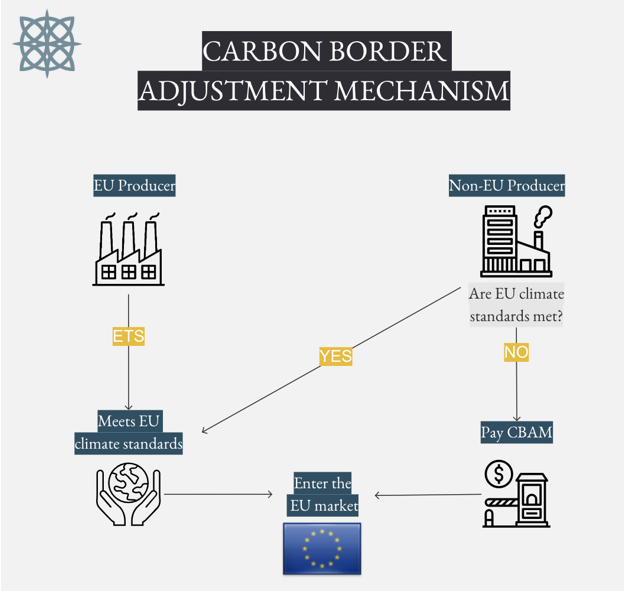

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) works by having EU importers buy carbon certificates that would’ve been bought had the goods been produced in the EU under the existing carbon pricing mechanism. Similarly, if a non-EU country can attest to paying a carbon price in the country of production, the corresponding CBAM cost can be reduced for the EU importer. The mechanism aims to minimize the risk of leakage while also incentivizing countries outside Europe to rethink their carbon intensive production processes to continue current trading patterns. The CBAM will be fully adopted by the EU in 2026 after a three-year phase in period. Initially, the CBAM will only cover Scope 1 emissions from imports of carbon intensive goods with a high risk of leakage namely—iron and steel, cement, fertilizer, aluminum, and electricity. After the initial phase in period, the policy’s effectiveness will be evaluated to determine its application to other goods and services. Over time, this measure is expected to replace the free allowances granted by the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), by equalizing the carbon costs associated with domestic and international production.

Copyright Apala Group LLC.

The CBAM aims to address the issue of carbon leakage by imposing an equal burden on stakeholders inside and outside the EU. However, the implications of the policy regarding trade would be felt disproportionately in different economies globally. Several Asian countries, part of the top 10 importers to the EU—China, South Korea, and India, initially viewed this policy in a negative light, perceiving the policy as protectionist and putting key developing Asian economies at a disadvantage. But given the nascent stages of the policy, the specific implications are yet to be understood fully. In APAC, China and India are among the countries expected to see the most consequences from the policy, including negative effects on GDP and lower investment in the region over the short run. To address this, some critics have suggested a redirection of CBAM revenue to these economies to help green their industries and help facilitate decarbonization efforts. Thus far, however, the EU has been clear that CBAM revenue will be recirculated into the EU budget to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall the general sentiment across non-EU countries (not just in Asia) has been for a collaborative and inclusive effort rather than an individualistic approach that comes off as protectionist.

Many questions about the policy remain. Will industries shift their production to non-EU countries with cleaner grids or will it result in a cleaner EU production grid? Could the exporter avoid/minimize the tax burden through purchase of renewable energy or offsets? Or does the country of production need to have a national carbon reduction mechanism in place to offset the CBAM? While the specific implications of the policy have yet to be fully understood, the transition period is expected to provide more clarity.

Join Apala Group’s Nidhi Gangavarapu at the upcoming panel at REM Asia on April 27 and our CBAM Market Briefing on May 3 for a deeper understanding of the policy and its implications.